- Tabletop games

- Board games

- Tile-based games

- Turn-based games.html

- Abstract strategy games

- card games

- Connection games

- Mancala games

- Paper-and-pencil games

- Word games

Play-by-mail games, or play-by-post games, are games, of any type, played through postal mail or email.

Correspondence chess has been played by mail for centuries. The boardgame Diplomacy has been played by mail since the 1960s, starting with a printed newsletter (a fanzine) written by John Boardman. More complex games, moderated entirely or partially by computer programs, were pioneered by Rick Loomis of Flying Buffalo in 1970. The first such game offered via major e-mail services was WebWar II (based on Starweb and licensed from Flying Buffalo) from Neolithic Enterprises who accepted e-mail turns from all of the major e-mail services including CompuServe in 1983.

Play by mail games are often referred to as PBM games, and play by email is sometimes abbreviated PBeM - as opposed to face to face (FTF) or over the board (OTB) games which are played in person. Another variation on the name is Play-by-Internet (PBI) or Play-by-Web (PBW). In all of these examples, player instructions can be either executed by a human moderator, a computer program, or a combination of the two.

In the 1980s, play-by-mail games reached their peak of popularity with the advent of Gaming Universal, Paper Mayhem and Flagship magazine, the first professional magazines devoted to play-by-mail games. (An earlier fanzine, Nuts & Bolts of PBM, was the first publication to exclusively cover the hobby.) Bob McLain, the publisher and editor of Gaming Universal, further popularized the hobby by writing articles that appeared in many of the leading mainstream gaming magazines of the time. Flagship later bought overseas right to Gaming Universal, making it the leading magazine in the field. Flagship magazine was founded by Chris Harvey and Nick Palmer (now an MP) of the UK. The magazine still exists, under a new editor, but health concerns have led to worries over the publication's long term viability.

In the late 1990s, computer and Internet games marginalized play-by-mail conducted by actual postal mail, but the postal hobby still exists with an estimated 2000-3000 adherents worldwide.

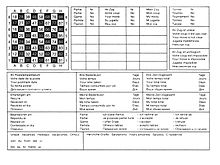

Postcard for international correspondence chess

Postcard for international correspondence chessPostal gaming developed as a way for geographically separated gamers to compete with each other. It was especially useful for those living in isolated areas and those whose tastes in games were uncommon.

In the case of a two player game such as chess, players would simply send their moves to each other alternately. In the case of a multi-player game such as Diplomacy, a central game master would run the game, receiving the moves and publishing adjudications. Such adjudications were often published in postal game zines, some of which contained far more than just games.

The commercial market for play-by-mail games grew to involve computer servers set up to host potentially thousands of players at once. Players would typically be split up into parallel games in order to keep the number of players per game at a reasonable level, with new games starting as old games ended. A typical closed game session might involve one to two dozen players, although some games claimed to have as many as five hundred people simultaneously competing in the same game world. While the central company was responsible for feeding in moves and mailing the processed output back to players, players were also provided with the mailing addresses of others so that direct contact could be made and negotiations performed. With turns being processed every few weeks (a two week turnaround being standard), more advanced games could last over a year.

Game themes are heavily varied, and may range from those based on historical or real events to those taking place in alternate or fictional worlds.

Inevitably, the onset of the computer-moderated PBM game (primarily the Legends game system) meant that the human moderated games became "boutique" games with little chance of matching the gross revenues that larger, automated games could produce.

The mechanics of play-by-mail games require that players think and plan carefully before making moves. Because planned actions can typically only be submitted at a fixed maximum frequency (e.g., once every few days or every few weeks), the number of discrete actions is limited compared to real-time games. As a result, players are provided with a variety of resources to assist in turn planning, including game aids, maps, and results from previous turns. Using this material, planning a single turn may take a number of hours.

Actual move/turn submission is traditionally carried out by filling in a turn card. This card has formatted entry areas where players enter their planned actions (using some form of encoding) for the upcoming turn. Players are limited to some finite number of actions, and in some cases must split their resources between these actions (so that additional actions make each less effective). The way the card is filled in often implies an ordering between each command, so that they are processed in-order, one after another. Once completed, the card is then mailed (or, in more modern times, emailed) to the game master, where it is either processed, or held until the next turn processing window begins.

By gathering turn cards from a number of players and processing them all at the same time, games can provide simultaneous actions for all players. However, for this same reason, co-ordination between players can be difficult to achieve. For example, player A might attempt to move to player B's current location to do something with (or to) player B, while player B might simultaneously attempt to move to player A's current location. As such, the output/results of the turn can differ significantly from the submitted plan. Whatever the results, they are mailed back to the player to be studied and used as the basis for the next turn (often along with a new blank turn card).

While billing is sometimes done using a flat per-game rate (when the length of the game is known and finite), games more typically use a per-turn cost schedule. In such cases, each turn submitted depletes a pool of credit which must periodically be replenished in order to keep playing. Some games have multiple fee schedules, where players can pay more to perform advanced actions, or to take a greater number of actions in a turn.

Some role-playing PBM games also include an element whereby the player may describe actions of their characters in a free text form. The effect and effectiveness of the action is then based on the judgement of the GM who may allow or partially allow the action. This gives the player more flexibility beyond the normal fixed actions at the cost of more complexity and, usually, expense.

With the rise of the Internet, email and websites have largely replaced postal gaming and postal games zines. Play-by-mail games differ from popular online multiplayer games in that, for most computerized multiplayer games, the players have to be online at the same time - also known as synchronous play. With a play-by-mail game, the players can play whenever they choose, since responses need not be immediate; this is sometimes referred to as turn-based gaming and is common among browser-based games. Some video games can be played in turn-based mode: one makes one's "move", then play for that player stops, and the turn passes to another player who to makes his or her move in response.

Several non-commercial email games played on the Internet and BITNET predate these.

Some cards games like poker can also be played by email using cryptography (see for example a patent application from FXTOP, another algorithm exists in Applied Cryptography from Bruce Schneier in case of 2 players

An increasingly popular format for play-by-email games is play-by-web. As with play-by-email games the players are notified by email when it becomes their turn, but they must then return to the game's website to continue playing what is essentially a browser-based game. The main advantage of this is that the players can be presented with a graphical representation of the game and an interactive interface to guide them through their turn. Since the notifications only have to remind the players that it is their turn they can just as easily be sent via instant messaging.

Some sites have extended this gaming style by allowing the players to see each other's actions as they are made. This allows for real time playing while everyone is online and active, or slower progress if not.

Increasingly, this format is being adopted by social and mobile games, often described using the term "asynchronous multiplayer."