Hammond Electric Bridge Table

Four bridge players

The Hammond Electric Bridge Table was an electromechanical automatic card shuffling machine that dealt playing cards at random to four bridge players. The mechanism was built into a card table. The main concept of the machine was as a labor saving aid for bridge players in dealing out the hands. The invention was an offspring from the Hammond Clock Company as an additional product. It was a popular device when first introduced at the pre-Christmas season of 1932. That was short lived, however, and production lasted only a couple of years.

Development

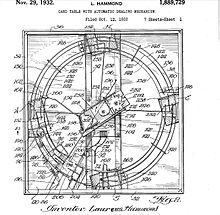

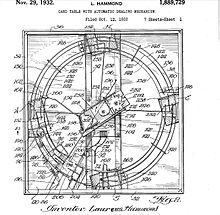

Hammond patented card mechanism within card table, November 29, 1932

The device has its origins with the Hammond Clock Company which was formed by Laurens Hammond in 1928 in Chicago, Illinois. By 1932, over one hundred clock companies had gone out of business due to the Great Depression but Hammond was determined to remain solvent and created new products for the company to sell. One such product was an automatic card dealer. Hammond was a bridge player and a mechanical engineer and he put the two together and invented the Hammond Electric Bridge Table. This was an automatic playing card dealing apparatus that was specifically designed for use in contract bridge. The electric bridge mechanism was patented on November 29, 1932 and the patent for the card table that contained it was filed the day before. It was the first bridge table to automatically shuffle and deal cards using electricity.

Production

Around 14,000 tables were made and a few thousand sold. The sales were so brisk during the Christmas season of 1932 that the Marshall Field's department store in Chicago had taxicabs waiting at the factory to pick up lots of four or five tables and deliver them immediately to the store for their pre-Christmas sales. In the month of December the profits from the electric bridge tables were $75,000 which saved the Hammond Clock Company temporarily. The price was $25. The deluxe model sold for $40. This was expensive for the time, as the income in the United States had fallen due to the depression. The electric bridge table was presented at the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago, but sales declined after that and within a couple of years production was discontinued altogether.

Description

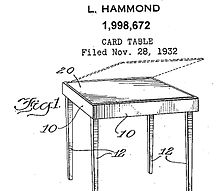

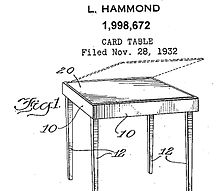

Hammond Card Table patent number 1,998,672 filed on November 28, 1932

The 28 inch square wooden card table was about 3 inches thick and looked like an ordinary bridge table. The table came in two models, a standard one of walnut finish to the legs and frame, and a deluxe model that additionally had matching veneer on the sides. They both came with a masonite removable top (see "Card Table" patent). Both models came with two electrical outlets under the table for an electrical cord to be plugged.

The table had a built-in electromechanical mechanism hidden within the top that was referred to as the "brain." It shuffled and dealt the cards automatically and gave a set of randomly picked bridge hands of four 13-card sets to each of the four players. Since the mechanism did the shuffling, it always came out with the correct amount of cards for each of the players. When the table came out it was considered the ultimate convenience in a play-aiding device since players no longer had to deal out by hand and it had the added benefit that cheating was impossible since the cards were dealt solely by the machine. The players would play bridge while another set of cards was being dealt out by the mechanism and dropping them at random into the four player bins where they retrieved their 13-card sets.

The deck of cards did not need shuffling beforehand. It was simply placed into a built-in card deck holder in the table top. One of the players would push in the holder which triggered a switch that started an electric motor within the mechanism. This then swung a mechanical arm clockwise that had a rubber finger attached. It then picked up the top card and passed it onto a second arm that decided which bridge player hand would get that card. It had 635,013,559,600 different combinations of cards that any one player could be dealt. It took about a minute for the electric bridge table mechanism to deal out to all four players the 13 cards required. The complicated mechanical gears and levers of the mechanism were referred to by Hammond as a "robot".

COMMENTS

Four bridge players

Four bridge players Hammond patented card mechanism within card table, November 29, 1932

Hammond patented card mechanism within card table, November 29, 1932 Hammond Card Table patent number 1,998,672 filed on November 28, 1932

Hammond Card Table patent number 1,998,672 filed on November 28, 1932