In computer science, Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) is a heuristic search algorithm of making decisions in some decision processes, most notably employed in game playing. The leading example of its use is in contemporary computer Go programs, but it is also used in other board games, as well as real-time video games and non-deterministic games such as poker (see history section).

MCTS concentrates on analysing the most promising moves, basing the expansion of the search tree on random sampling of the search space. MCTS in games is based on many playouts. In each playout, the games are played-out to the very end by selecting moves at random. The final game result of each playout is then used to weight the nodes in the game tree so that better nodes are more likely to be chosen in future playouts.

The most primitive way of using playouts is playing the same number of them after each legal move of the current player and choosing the move, after which the most playouts ended up in the player's victory. The efficiency of this method - called Pure Monte Carlo Game Search - often increases when, as time goes on, more playouts are assigned to the moves that have frequently resulted in the player's victory (in previous playouts). Full MCTS consists in employing this principle recursively on many depths of the game tree. Each round of MCTS consists of four steps:

, select successive child nodes down to a leaf node

, select successive child nodes down to a leaf node  . The section below says more about a way of choosing child nodes that lets the game tree expand towards most promising moves, which is the essence of MCTS.

. The section below says more about a way of choosing child nodes that lets the game tree expand towards most promising moves, which is the essence of MCTS. ends the game by resulting in a win/loss for either player, either create one or more child nodes of it and choose from them node

ends the game by resulting in a win/loss for either player, either create one or more child nodes of it and choose from them node  .

. .

. to

to  .

.Sample steps of one round are shown in the figure below. Each tree node stores the number of won/played playouts.

Note that the updating of the number of wins in each node during backpropagation should be from the point of view of the player who made the move that resulted in that node (this is not accurately reflected in the sample image above). This ensures that during selection, each player chooses to expand towards the most promising moves for that player, which mirrors the maximizing behavior of each player in reality.

Such rounds are repeated as long as the time allotted to a move is not up. Then, one of moves from the root of the tree is chosen but it is the move with the most simulations made rather than the move with the highest average win rate.

This basic procedure can be applied in all games which have only positions with finitely many moves, and which allow only for games of finite length. In a position all feasible moves are determined, for each one k random games are played to the very end, and the cumulative scores are recorded. The move with the best score is chosen. Ties are broken by fair coin flips. Pure Monte Carlo Game Search results in strong play in several games with random elements, for instance in EinStein würfelt nicht!. It converges to optimal play (as k tends to infinity) in board filling games with random turn order, for instance in Hex with random turn order.

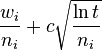

The main difficulty in selecting child nodes is maintaining some balance between the exploitation of deep variants after moves with high average win rate and the exploration of moves with few simulations. The first formula for balancing exploitation and exploration in games, called UCT (Upper Confidence Bound 1 applied to trees), was introduced by L. Kocsis and Cs. Szepesvári basing on the UCB1 formula derived by Auer, Cesa-Bianchi, and Fischer. Kocsis and Szepesvári recommend to choose in each node of the game tree the move, for which the expression  has the highest value. In this formula:

has the highest value. In this formula:

stands for the number of wins after the

stands for the number of wins after the  th move;

th move; stands for the number of simulations after the

stands for the number of simulations after the  th move;

th move; is the exploration parameter - theoretically equal to

is the exploration parameter - theoretically equal to  ; in practice usually chosen empirically;

; in practice usually chosen empirically; stands for the total number of simulations, equal to the sum of all

stands for the total number of simulations, equal to the sum of all  .

.The first component of the formula above corresponds to exploitation; it is high for moves with high average win ratio. The second component corresponds to exploration; it is high for moves with few simulations.

Most contemporary implementations of MCTS are based on some variant of UCT.

Although it has been proven that the evaluation of moves in MCTS converges to the minimax evaluation, the basic version of MCTS can converge to it after enormous time. Besides this disadvantage (partially cancelled by the improvements described below), MCTS has some advantages compared to alpha-beta pruning and similar algorithms.

Unlike them, MCTS works without an explicit evaluation function. It is enough to implement game mechanics, i.e. the generating of allowed moves in a given position and the game-end conditions. Thanks to this, MCTS can be applied in games without a developed theory or even in general game playing.

The game tree in MCTS grows asymmetrically: the method concentrates on searching its more promising parts. Thanks to this, it achieves better results than classical algorithms in games with a high branching factor.

Moreover, MCTS can be interrupted at any time, yielding the move it considers the most promising.

Various modifications of the basic MCTS method have been proposed, with the aim of shortening the time to find good moves. They can be divided into improvements based on expert knowledge and into domain-independent improvements.

MCTS can use either light or heavy playouts. Light playouts consist of random moves. In heavy playouts various heuristics influence the choice of moves. The heuristics can be based on the results of previous playouts (e.g. the Last Good Reply heuristic) or on expert knowledge of a given game. For instance, in many go-playing programs, certain stone patterns on a part of the board influence the probability of moving into that part. Paradoxically, not always playing stronger in simulations makes an MCTS program play stronger overall.

Patterns of hane (surrounding opponent stones) used in playouts by the MoGo program. It is advantageous both for black and for white to put a stone on the middle square, except the rightmost pattern where it is advantageous for black only.

Patterns of hane (surrounding opponent stones) used in playouts by the MoGo program. It is advantageous both for black and for white to put a stone on the middle square, except the rightmost pattern where it is advantageous for black only.Domain-specific knowledge can also be used while building the game tree, to help the exploitation of some variants. One of such methods consists in assigning nonzero priors to the numbers of won and played simulations when creating a child node. Such artificially raised or lowered average win rate causes the node to be chosen more or less frequently, respectively, in the selection step. A related method, called progressive bias, consists in adding to the UCB1 formula a  element, where

element, where  is a heuristic score of the

is a heuristic score of the  th move.

th move.

The basic MCTS collects enough information to find the most promising moves after many rounds. Before that, it chooses more or less random moves. This initial phase can be significantly shortened in a certain class of games thanks to RAVE (Rapid Action Value Estimation). The games in question are those where permutations of a sequence of moves lead to the same position, especially board games where a move consists in putting a piece or a stone on the board. In such games, the value of a move is often only slightly influenced by moves played elsewhere.

In RAVE, for a given game tree node  , its child nodes

, its child nodes  store besides the statistics of wins in playouts started in node

store besides the statistics of wins in playouts started in node  also the statistics of wins in all playouts started in node

also the statistics of wins in all playouts started in node  and below it, if they contain move

and below it, if they contain move  (also when the move was played in the tree, between node

(also when the move was played in the tree, between node  and a playout). This way, the contents of tree nodes are influenced not only by moves played immediately in a given position but also by the same moves played later.

and a playout). This way, the contents of tree nodes are influenced not only by moves played immediately in a given position but also by the same moves played later.

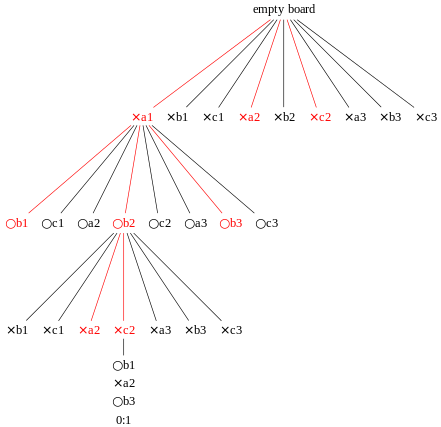

RAVE on the example of tic-tac-toe. In red nodes, the RAVE statistics will be updated after the b1-a2-b3 simulation.

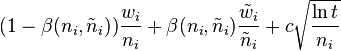

RAVE on the example of tic-tac-toe. In red nodes, the RAVE statistics will be updated after the b1-a2-b3 simulation.When using RAVE, the selection step selects the node, for which the modified UCB1 formula  has the highest value. In this formula,

has the highest value. In this formula,  and

and  stand for the number of won playouts containing move

stand for the number of won playouts containing move  and the number of all playouts containing move

and the number of all playouts containing move  , and the

, and the  function should be close to one and to zero for relatively small and relatively big

function should be close to one and to zero for relatively small and relatively big  and

and  , respectively. One of many formulas for

, respectively. One of many formulas for  , proposed by D. Silver, says that in balanced positions one can take

, proposed by D. Silver, says that in balanced positions one can take  , where

, where  is an empirically chosen constant.

is an empirically chosen constant.

Heuristics used in MCTS often depend on many parameters. There are methods of automatic tuning the values of these parameters to maximize the win rate.

MCTS can be concurrently executed by many threads or processes. There are several fundamentally different methods of its parallel execution:

The Monte Carlo method, based on random sampling, dates back to the 1940s. Bruce Abramson explored the idea in his 1987 PhD thesis and said it "is shown to be precise, accurate, easily estimable, efficiently calculable, and domain-independent." He experimented in-depth with Tic-tac-toe and then with machine generated evaluation functions for Othello and Chess. In 1992, B. Brügmann employed it for the first time in a go-playing program, but his idea was not taken seriously. In 2006, called the year of the Monte Carlo revolution in Go, R. Coulom described the application of the Monte Carlo method to game-tree search and coined the name Monte Carlo tree search, L. Kocsis and Cs. Szepesvári developed the UCT algorithm, and S. Gelly et al. implemented UCT in their program MoGo. In 2008, MoGo achieved dan (master) level in 9x9 go, and the Fuego program began to win with strong amateur players in 9x9 go. In January 2012, the Zen program won 3:1 a 19x19 go match with John Tromp, a 2 dan player.

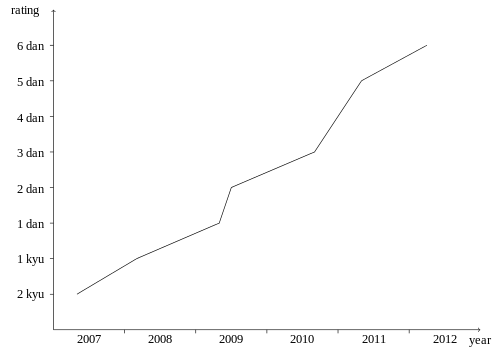

The rating of best go-playing programs on the KGS server since 2007. Since 2006, all the best programs use MCTS.

The rating of best go-playing programs on the KGS server since 2007. Since 2006, all the best programs use MCTS.MCTS has also been used in programs that play other board games (for example Hex, Havannah, Game of the Amazons, and Arimaa), real-time video games (for instance Ms. Pac-Man, Fable Legends and Total War: Rome II), and nondeterministic games (such as skat, poker, Magic: The Gathering, or Settlers of Catan).