Within most systems and at most levels, handicap is given to offset the strength difference between players of different ranks in the game of Go.

In the game of Go, a handicap is given by means of stones and compensation points. In contrast to an even game, in which Black plays first, White plays the first move in a game with handicap (after Black's handicap stones have been placed).

The rank difference within a given amateur ranking system is one guide to how many handicap stones should be given to make the game a more equal contest. As a general rule, each rank represents the value of one stone. (In terms of points, one stone is considered to be 13-16 points, but this figure is not constant over levels: the more skillful a player, the greater the usefulness of each stone.)

For example, a 3 kyu player gives a 7 kyu player four handicap stones to allow for an interesting game with roughly equal challenge for both players. If traditional fixed placement of the handicap stones is used, nine stones is normally the maximum handicap. Larger handicaps are certainly possible; but with such a great difference in strength, Black may be simply bewildered, and not understand how many of White's moves relate to his own.

The above rank relationship reliably applies for single-digit kyu (1-9k) and amateur dan (1-7d) ranks. The advantage of moving first is equivalent to only half a stone of handicap, as the opponent then has the initiative. Because White gets the next move after Black places the handicap stones, a nominal handicap of n stones is therefore in reality half a stone less than n.

Nowadays professional ranks are awarded by professional go players' organizations; they are, unlike amateur ranks, not reliable as a measure of current playing strength, but rather an indication of achievements. Before the late 20th century, they were used as strength measurement, with a difference in skill of less than a third of a stone per rank.

Small boards are often used for novice players (double-digit kyu players) just learning to play Go, or for quick games. As the fewer moves made when playing on smaller boards gives White fewer chances to overcome the advantage conferred by the handicap, smaller handicaps are used on smaller go boards (most commonly 13x13 and 9x9).

The per-rank handicap is therefore reduced, by a scaling factor. Various estimates have been given for the factor that applies to 13x13, in the range 2.5 up to 4; and on grounds both theoretical and experimental (small-board tournament play). The evidence is that 2.5 is more realistic than 4, for clock games. The corresponding factor for a 9x9 board is not easy to understand, and the change for each stone added is very large.

One theoretical approach is according to the distribution of the number of moves made in a game on a board of a given size relative to the number made on a 19x19 board. Using estimates that a 19x19 game will last about 250-300 moves, a 13x13 game about 95-120 moves, and a 9x9 game about 40-50 moves, a quadratic formula for the ratio of the mean number of plays may apply. Arguing that White catches up by means of Black's 'small errors', so that White's deficit drifts at a constant rate, it makes sense to take the ratio of game lengths as scaling factor.

Each full stone of handicap on a 13x13 board is in any case probably equivalent to about 2.5 to 3 ranks, and each full stone on a 9x9 board is equivalent to about 6 ranks. For example, if the appropriate handicap is 9 (i.e., 8.5) stones on a 19x19 board, the handicap between those two players is reduced to 4 (because 3.5 x 2.5 = 8.75) stones on a 13x13 board and 2 (1.5 x 6 = 9) stones on a 9x9 board. A 5 (i.e., 4.5) stone handicap on a 9x9 board is accordingly equivalent to a handicap of 27 or 28 stones on a 19x19 board.

These figures are not a consensus, but have wide support. They can be used to give rankings, by converting 13x13 handicaps back to rank difference.

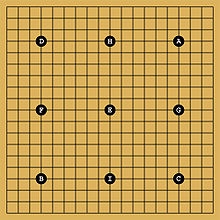

The traditional placement of handicap stones

The traditional placement of handicap stonesThere are 9 star points marked on a 19 x 19 board - in each corner on the (4,4) point, in the middle of each side on the fourth line, (4,10); and the very center of the board, (10,10). Traditionally handicaps are always placed on the star points, as follows:

| Stones | Placement | Locations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Black plays his first stone as he wishes, and gives no komi | None |

| 2 | Black plays the star points to his upper right and lower left | A,B |

| 3 | Black adds the star point to his lower right (In Classical Chinese rules the third handicap stone is place on tengen) | A,B,C (or E) |

| 4 | Black takes all four corner star points | A,B,C,D |

| 5 | Black adds the center star point | A,B,C,D,E |

| 6 | Black takes all three star points at left and right | A,B,C,D,F,G |

| 7 | Black adds the center star point | A,B,C,D,E,F,G |

| 8 | Black takes all star points except the center | A,B,C,D,F,G,H,I |

| 9 | Black takes all nine star points | A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H,I |

As the stones are always at the same (4,4) points in the corners, Black always plays more (4,4) openings, and doesn't gain experience playing the (3,4) openings, or others such as (3,3), (5,4), (5,3), etc., except on two and three stones.

Recently, some have advocated free placement of handicap stones. Free placement means one can place handicap stones anywhere on the board without restriction. Here is the list of countries and servers that use free placement of handicap stones:

| Fixed Placement | Japan, Korea, United States (by default), IGS online server |

|---|---|

| Free Placement | Chinese, Ing, New Zealand |

Although free placement is less common because many players are attached to tradition, especially in East Asian countries, it offers advantages which are not available with fixed placement.

For weaker players:

For stronger players:

With free placement, weaker players may not place their stones in respect to their comparable handicap to their opponent, thus eliminating the point of the handicap. The standard fixed handicap points allow for a good standard that allows novices to have the handicap they need since they are not experienced and may not be able to take advantage of the free placement of handicap stones. Therefore, free placement handicap may be best suited for more experienced players or those who want more flexibility and variety in play.

Read main article: Komidashi

When the difference in strength is one rank, no handicap stone is given. Instead the stronger player takes White but without compensation points. The compensation points are called Komi in Japanese. It is a custom that Black plays first; White moves second. Playing first is regarded as a significant advantage in modern go, and to make the game fair to both players, this advantage must be compensated. It is regarded that playing first is equal to half a move or more ahead throughout the game.

Another common type of compensation used is the reverse compensation points, where the weaker player takes black, and is given both the first move and compensation points too. This is more advantageous than the above situation.

Compensation points are sometimes preferred to stones because the players would like to play or practice as if it is an even game. They would like to have the feel of an "even game". White (the stronger player) must play better to overcome these disadvantages (points gained by playing first + compensation points).

When ranks are equal, Black gets advantages by playing first. The advantage of that first move is compensated by compensation points. However, there are still no absolute standards on the number of compensation points due to the difficulty of determining a fair value. 6.5 points are used in Japan and Korea. 7.5 points are used in China and America (see AGA rules). The 0.5 point is used to prevent a draw.

As no one can be absolutely sure what the fair number of compensation points is, some advocate another system which is often used in some amateur matches and tournaments. There are no fixed compensation points. The decision is left to both players. They arrive at a value through negotiation and bidding. This is called auction compensation point system.

Examples of auction komi systems include:

Handicap go is the traditional form of teaching given to go players. Fixed handicap placements are in effect a form of graded tutorials: if you cannot beat your teacher with a nine-stone handicap, some fundamental points are still to be learned.

The pedagogic value of fixed handicaps is an old debate for Western players. The 'theory' of handicap go shares with much of the rest of the Japanese pedagogic go literature a less explicit approach, based on perception as much as analysis. Whether fixed handicap placement makes it easier or more difficult for the weaker player to learn these fundamental points is moot. The nature of these 'tutorial' steps may certainly be misunderstood and contested by Western players new to the game. Handicaps are also unpopular with Chinese players, who have more of a tradition of equality at the board rather than deference to a teacher.

There are some book treatments of low-handicap go by strong professionals (Kobayashi Koichi and Kajiwara Takeo, in particular); and examples of pro-pro games to follow. With the traditional handicap placements, the only consistent strategy Black can follow depends on the use of influence. This is particularly true in the early stages of the middle-game fighting.

While Black often assumes that consolidating territory from the opening stages should be enough to win, that is not the case when the handicap stones are placed on the star points, where they are more effective in obtaining influence than territory. If Black does not understand and utilize the value of star-point handicap stones for attack, White will gradually build a more advantageous position, and steadily close the gap.